As word of Ambedkar's newspaper spread, Kolhapur’s Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj himself visited Babsaheb in his chawl in Mumbai, offering a donation of Rs 2,500 to start Mooknayak. The first issue was printed on 31 January 1920

As word of Ambedkar's newspaper spread, Kolhapur’s Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj himself visited Babsaheb in his chawl in Mumbai, offering a donation of Rs 2,500 to start Mooknayak.

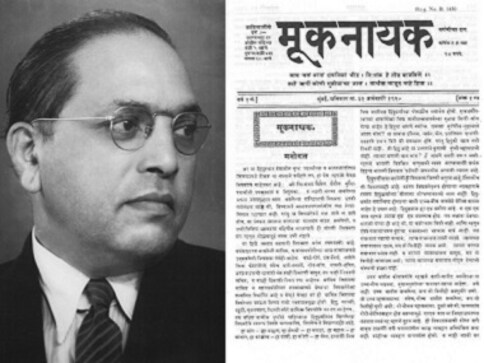

The first issue was printed on 31 January 1920.

It included a scathing takedown of the Hindu caste structure and its despicable advocacy of inequality.

The year was 1920. Dr BR Ambedkar was working as a government servant, having returned to India a while ago, leaving a course midway in London after his Baroda State Scholarship ended. Babasaheb had already earned a Master’s degree and a Doctorate in the US by that time, but he was anxious to return to the UK and complete his studies towards a second doctoral degree.

Since his return in 1917, he had been trying to work and save enough money towards that end; it was an eventful time. Between 1918-19, the Southborough Committee had invited Babasaheb to testify before it, on behalf of untouchables. Alongside Ambedkar, Vitthal Ramji Shinde — an upper caste social worker — had also been asked to present his testimony. When the newspapers published the proceedings, Shinde’s testimony received significant space. Babsaheb’s — despite his recommendations on reservations and a separate electorate — did not. In January 1919, Babasaheb sent a letter to The Times of India, under the pseudonym ‘Ek Mahar’; the newspaper did not publish his letter. To Babasaheb, these were examples of the media’s prejudiced views under the British Raj.

Another notable incident was when he sent BG Tilak’s Kesari a note for an advertisement along with a Rs 3 publishing fee. Tilak neglected to publish the note, and returned the fee. Babasaheb was by then convinced that the Brahmanical media would never consider the problems of untouchables as important, and of national significance. Babasaheb decided that he would start his own newspaper — a weekly, devoted to the issues and challenges of untouchables. He named it Mooknayak (leader of the dumb).

All of Mooknayak’s editorials were written by Babasaheb himself, although they did not carry his byline since he was in government service at the time

As word of the newspaper spread, Kolhapur’s Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj himself visited Babsaheb in his chawl in Mumbai, offering a donation of Rs 2,500 to start Mooknayak. The first issue was printed on 31 January 1920 and included a scathing takedown of the Hindu caste structure and its despicable advocacy of inequality. “Hindu society is like a building. And each caste is one floor in it. But the thing to be remembered is that this building has no stairs. And hence there is no way to go from one floor to another. Those who are born in their floor should die in their respective floors. If a person is from the floor below, no matter how eligible he is, he cannot go to the floor above. And a person from the floor above — no matter how useless he may be — no one has the wisdom/courage to bring him down,” Babasaheb wrote. Apart from his editorial, the issue also carried couplets from 13th century poet-saint Tukaram’s abhanga.

Today, 31 January 2020, marks 100 years of Mooknayak. Celebrations have been planned at Ambedkar Bhavan in Mumbai, for 1 February, to mark the occasion. The short-lived newspaper’s indelible impact may not be evident to those unaware of the history of the Dalit movement, and it would require paying heed to the words of writer and historian JV Pawar, or Ramesh Shinde — a bibliophile who has all the editions of Babasaheb’s books, including the first and the only edition of his doctoral theses (published by a reputed London press in the 1920s). According to Pawar, it was “because of Mooknayak [that] the atmosphere of fear among untouchables faded and because of Babasaheb’s initiative that they [untouchables], now Dalits, acquired a sense of dignity and self-respect as well as confidence”.

All of Mooknayak’s editorials were written by Babasaheb himself, although they did not carry his byline since he was in government service at the time. Remarkably, Mooknayak was published in Marathi, and the weekly played an instrumental role in developing reading habits among Dalits. Those who could not read would ask others to read it aloud to them. And thus, Babasaheb’s thoughts were communicated to them, preparing them for the biggest battle of all — the battle to reclaim human personality, lost under the cruel reign of ‘untouchability’.

With Mooknayak, the silence of the untouchables was shattered.

SOURCE:https://www.firstpost.com/living/mooknayak-turns-100-how-babasaheb-ambedkars-marathi-weekly-for-dalits-came-into-being-7983101.html

No comments:

Post a Comment